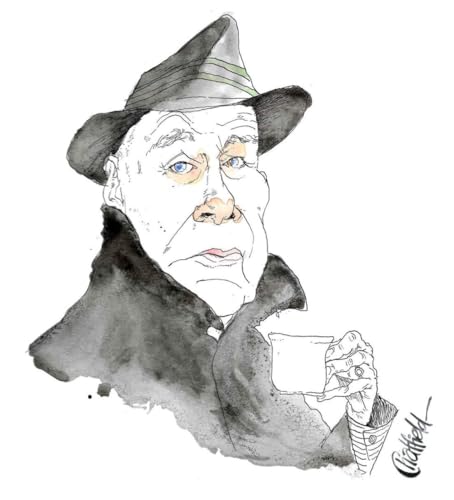

The Watercolour Control Problem with Jessie Kanelos Weiner

This week, I joined Jessie Kanelos Weiner —artist, author, and watercolour wizard—for a live chat about colour, chaos, and why watercolour refuses to obey. She just released Thinking in Watercolour, which made me realise I mostly think in ink, panic, and snacks.

Jessie asked how I approach colour, and I admitted that I approach it sparingly. I used to think “real artists” painted every shadow like da Vinci. Then I saw the da Vincis at the Met and thought, Yeah… I don’t need to do all that. These days, I use colour the way comedians use silence—strategically. A dab here, a spot there. Enough to make you look where I want you to look.

We talked about the Philadelphia Eagles poster I illustrated—a parody of the classic New Yorker cover, except it’s a jacked football player instead of Eustace Tilly. They wanted bold colour. I gave them subtle pastels amid the team’s green hue. They said, “Brighter!” I spent two days repainting and relearned my favourite rule: colour should serve the joke, not the marketing department.

Growing up in Perth, I had almost no access to great art—just beach paintings and dial-up internet. So I learned from cartoonists like Roz Chast, Richard Thompson, and Ronald Searle, whose trauma and humour somehow coexisted in ink. My grandfather gave me Searle’s book after surviving a POW camp, so I guess drawing as coping runs in the family.

Jessie and I agreed: restriction is, in fact, a form of freedom. Fewer colours, fewer brushes, fewer excuses. Watercolour is chaos in liquid form, and the sooner you stop trying to control it, the more alive it becomes.

I’m still working on that part—the unclenching. But at least now, when my washes go rogue, I can say: It’s philosophy.

‘til next timeyour pal,

✏️ Thanks for reading New York Cartoons. To support more chaos disguised as art, consider becoming a paid subscriber.

This is a public episode. If you'd like to discuss this with other subscribers or get access to bonus episodes, visit www.newyorkcartoons.com/subscribe

34 分

34 分 2025/10/0858 分

2025/10/0858 分 2025/10/0657 分

2025/10/0657 分

1 時間 2 分

1 時間 2 分